30 dezembro 2016

21 dezembro 2016

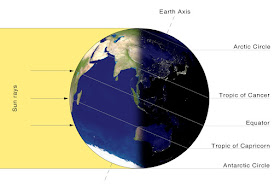

SOLSTÍCIO DE VERÃO

A Terra - The Earth.

Solstício de Verão é um fenômeno da astronomia que marca o início do Verão.

É o instante em que determinado hemisfério da Terra está inclinado cerca de 23,5º na direção do Sol, fazendo com que receba mais raios solares.

O termo “solstício” tem a sua origem no latim solstitius que significa "ponto onde a trajetória do sol aparenta não se deslocar".

No solstício de Verão ocorre o dia mais longo do ano e, consequentemente, a noite mais curta, em termos de iluminação por parte dos raios Sol.

O solstício acontece graças aos fenômenos de rotação e translação do planeta Terra, pois graças a eles a luz solar é distribuída de forma desigual entre os dois hemisférios.

Solstício de verão (1 min. 30 seg.).

Solstício de Verão no Hemisfério Sul

Quando o hemisfério sul está passando pelo solstício de verão – evento que marca o início desta estação – as pessoas que vivem no hemisfério norte da Terra estão passando pelo solstício de inverno, considerado o dia com a noite mais longa do ano.

O solstício de Verão pode acontecer no dia 21 ou 22 de dezembro, dias em que a radiação solar incide de forma vertical sobre o Trópico de Capricórnio no Hemisfério Sul.

O Brasil está localizado no Hemisfério Sul (meridional), enquanto que a Europa e os Estados Unidos, por exemplo, fazem parte do Hemisfério Norte (setentrional).

Ilustração: Solstício de Verão e Solstício de Inverno.

Solstício de Inverno

Enquanto que o solstício de Verão marca o início do Verão, o solstício de inverno é conhecido por marcar o começo do inverno.

O solstício de Inverno significa que a luz do sol não incide com tanto fulgor no hemisfério em questão.

Saiba mais sobre o significado do Solstício de Inverno.

Equinócios

O equinócio, assim como o solstício, também é um acontecimento astronômico, que marca o início do Outono e da Primavera.

Situação de incidência dos raios solares perpendicularmente ao Trópico de Capricórnio, caracterizando o Solstício de Verão no Hemisfério Sul (Meridional) e por conseguinte o Solstício de Inverno no Hemisfério Norte (Setentrional).

18 dezembro 2016

02 dezembro 2016

CURSO NO IIPC (SP)

AUTOSSUPERAÇÃO DO ORGULHO

(CURSO LIVRE)

Orgulho é um traço fardo (TRAFAR) inibidor da manifestação autêntica da consciência, fazendo com que ela esteja sempre na defensiva de sua autoimagem, é uma maneira de esconder suas fragilidades, se autossabotando e impedindo ou limitando a interação com outras consciências, e assim boicotando a própria evolução.

OBJETIVOS ESPECÍFICOS

Data do evento: 10 de dezembro de 2016.

Horário: das 14h00 às 19h30.

Local: Rua Afonso Celso, n° 587, Vila Mariana, São Paulo, SP - próximo ao metrô Santa Cruz.

INFORMAÇÕES

(011) 3387-9705

(011) 3387-9706

(011) 97364-1138

e-mail: saopaulo@iipc.org

(CURSO LIVRE)

Orgulho é um traço fardo (TRAFAR) inibidor da manifestação autêntica da consciência, fazendo com que ela esteja sempre na defensiva de sua autoimagem, é uma maneira de esconder suas fragilidades, se autossabotando e impedindo ou limitando a interação com outras consciências, e assim boicotando a própria evolução.

OBJETIVOS ESPECÍFICOS

- Entender algumas posturas de comportamento orgulhoso;

- Trazer ferramentas para identificação dos traços fardos mais impactantes da consciência, analisando os traços fardos (TRAFARES) sintomas;

- Analisar os resultados patológicos na junção do traços força (TRAFOR) e a postura orgulhosa;

- Verificar a importância da qualificação da lealdade como ferramenta para a autosuperação desse trafar;

- Buscar o desenvolvimento do binômio admiração-discordância;

- Entender a falácia da afirmação do lado positivo do orgulho;

- A necessidade do desenvolvimento da convivialidade sadia e interassistência.

Data do evento: 10 de dezembro de 2016.

Horário: das 14h00 às 19h30.

Local: Rua Afonso Celso, n° 587, Vila Mariana, São Paulo, SP - próximo ao metrô Santa Cruz.

INFORMAÇÕES

(011) 3387-9705

(011) 3387-9706

(011) 97364-1138

e-mail: saopaulo@iipc.org

⇛ Visite o site do IIPC: www.iipc.org

29 novembro 2016

NOTA

Sobre o acidente ocorrido com o

time da Chapecoense, temos MEDIDAS SOLIDARIAS que estão sendo adotadas por

clubes do futebol brasileiro.

Fifa, Conmebol e CBF emitem notas sobre acidente com avião da Chapecoense

Fonte: Esporte - iG @ http://esporte.ig.com.br/2016-11-29/notas-sobre-acidente-chapecoense.html

Por exemplo, Palmeiras e

Corinthians apresentam exatamente a mesma nota sobre as MEDIDAS SOLIDÁRIAS que podem ser vistas nos seus sites (Palmeiras / Corinthians) e que

segue copiada abaixo:

Neste momento de perda e de profunda

tristeza, nós, presidentes dos clubes brasileiros que publicam esta nota,

gostaríamos de manifestar nossos mais sinceros sentimentos de pesar e

solidariedade à Associação Chapecoense de Futebol e seus torcedores, e em

especial às famílias e amigos dos atletas, comissão técnica e dirigentes

envolvidos na tragédia ocorrida na madrugada desta terça-feira (29).

Mesmo cientes dos prejuízos

irreparáveis provocados por este terrível acontecimento, os clubes entendem que

o momento é de união, apoio e auxílio à Chapecoense.

Neste sentido, os clubes anunciam

Medidas Solidárias à Chapecoense, que consistirão, dentre outras, em:

(i) Empréstimo gratuito de atletas

para a temporada de 2017; e

(ii) Solicitação formal à

Confederação Brasileira de Futebol para que a Chapecoense não fique sujeita ao

rebaixamento à Série B do Campeonato Brasileiro pelas próximas 3 (três)

temporadas. Caso a Chapecoense termine o campeonato entre os quatro últimos, o

16º colocado seria rebaixado.

Trata-se de gesto mínimo de

solidariedade que se encontra ao nosso alcance neste momento, mas dotado do

mais sincero objetivo de reconstrução desta instituição e de parte do futebol

brasileiro que fora perdida hoje.

#ForçaChape

11 novembro 2016

SETE BREVES LIÇÕES DE FÍSICA (Seven Brief Lessons on Phisycs)

7 conceitos da Física 'simplificados'

Uma obra que trata de mecânica quântica, partículas elementares, arquitetura do cosmo e buracos negros, entre outros temas de física teórica, está há meses na lista de livros mais vendidos na Itália.

Em Sete Breves Lições de Física (publicado no Brasil pela Ed. Objetiva), o professor Carlo Rovelli resume de modo simples os principais conceitos da ciência contemporânea, desde a teoria da relatividade geral de Albert Einstein, passando pelas descobertas do astrofísico inglês Stephen Hawking, até a provável extinção da espécie humana.

"A maior parte dos livros de física são escritos para quem já é apaixonado pelo assunto e quer saber mais. Por isso, pensei num livro para quem conhece pouco ou nada sobre a matéria. Poupei os detalhes e concentrei-me no essencial", disse o autor à BBC Brasil.

"É como escrever poesia: quanto mais se tira, mais bonita ela fica."

Nascido em Verona, no norte da Itália, e atual responsável pelo centro de pesquisas sobre gravidade quântica da Universidade Aix-Marseille, na França, Rovelli explica que o ensaio não trata apenas de física, mas de temas relacionados à natureza humana.

"O livro oferece uma possível resposta, do ponto de vista científico, às perguntas que todos nós, vez ou outra, nos fazemos durante a nossa vida: 'quem somos?', 'de onde viemos?', 'o que existe além daquilo que enxergamos?'. É a visão de alguém que se esforça para compreender isso tudo."

O sucesso da obra superou as expectativas da editora, que inicialmente havia imprimido três mil cópias. Passado pouco mais de um ano, o livro está em sua 18ª edição, teve 300 mil exemplares vendidos no país e foi traduzido para 28 idiomas.

Relatividade no horário nobre

"Logo depois do lançamento, comecei a receber e-mails de leitores entusiasmados, dizendo que comprariam outros exemplares para darem de presente. Em pouco tempo, o título apareceu na lista dos mais vendidos, algo estranho para uma obra de física teórica e, a partir daí, a coisa explodiu: editoras, jornais, rádios e revistas começaram a me procurar."

O professor, de 59 anos, chegou a falar sobre a teoria da relatividade de Einstein e de gravidade quântica em programas do horário nobre da televisão italiana. "Na verdade, as TVs passaram a me convidar só depois que o livro fez sucesso. Do contrário, acho que não teriam dado espaço para assuntos difíceis como este."

Também nas escolas, segundo Rovelli, falar sobre física é quase sempre "chato".

"Os períodos de férias são os melhores para se estudar, porque não há a distração da escola", diz, em um trecho do livro sobre o período em que era estudante universitário e, em uma praia da Calábria, leu pela primeira vez "a mais bela das teorias" (a da relatividade, de Albert Einstein), em um livro roído por ratos.

"Em vez de programas curriculares muito extensos e precisos, para atrair o interesse dos jovens pela ciência é necessário tratar bem os professores e deixar que eles tenham mais liberdade para abordarem os temas que mais gostam. O que faz um aluno se apaixonar por uma determinada matéria é o entusiasmo do próprio professor", afirma.

"Para compreender a ciência é preciso um pouco de empenho e esforço, mas o prêmio é a beleza. E olhos novos para enxergar o mundo."

Confira alguns trechos das explicações de Rovelli sobre personagens, teorias e conceitos da física:

Copérnico:

"Se eu quiser explicar a Revolução Copernicana, posso falar durante horas, apresentar cálculos e citar exemplos. Mas também posso dizer apenas que (Nicolau) Copérnico descobriu que a Terra gira em torno do Sol, e não o contrário. Este é o coração da descoberta, e isto as pessoas entendem."

Darwin:

"Outra extraordinária descoberta científica que pode ser explicada em poucas palavras é a teoria de (Charles) Darwin, que escreveu um livro difícil com pesquisas de observação, mas cuja revelação é simples: os seres humanos e todos os animais e plantas têm os mesmos antepassados, somos todos parentes."

Teoria da relatividade geral:

"Albert Einstein descobriu que o tempo e o espaço não são como acreditávamos até então. Ele nos ensinou que o tempo passa mais rápido no alto e mais lento embaixo, perto da Terra. Por isso, se dois irmão gêmeos viverem em lugares diferentes, um próximo ao mar e outro em montanha, e se reencontrarem depois de cinquenta anos, o que morava na montanha será um pouquinho mais velho que o irmão. Esta diferença pode ser medida até mesmo a uma altura de 30 centímetros do chão.

Einstein ensinou também que o espaço e a força de gravidade (descoberta por Newton) são a mesma coisa. O espaço não é mais diferente da matéria. É uma entidade que oscila, se dobra, se inclina e se torce. Como uma bolinha que roda dentro de um funil, não existem forças misteriosas geradas no centro do objeto, é a curva das paredes do funil que faz com que a bolinha rode. Do mesmo modo, os planetas giram em torno ao Sol e as coisas caem porque o espaço se inclina."

Tempo:

"Não existe ainda uma resposta final da ciência sobre o que é o tempo. Em todo caso, podemos dizer que ele não passa se nada acontece. O tempo não existe por si só, mas é ligado ao modo como as coisas se relacionam umas com as outras. Em vez de dizer que hoje peguei o avião às oito da manhã para vir a Roma, posso dizer que peguei o avião quando o Sol estava a uma certa altura e cheguei quando o Sol estava em outra posição. O tempo não é fundamental para o universo, é possível descrever a natureza sem usar o conceito de tempo."

Buracos negros:

"Quando uma grande estrela queima todo o seu combustível (hidrogênio), acaba por apagar-se. O que resta, então, não é mais suportado pelo calor da combustão e cai esmagado pelo seu próprio peso, inclinando o espaço tão fortemente a ponto de afundar dentro de um verdadeiro buraco. Estes são os famosos buracos negros."

Partículas elementares:

"O mundo é feito de pequenas entidades, os 'quanta', que vibram e saltam de lugar a outro. Existem menos de uma dezena de tipos de partículas elementares. Um punhado de ingredientes elementares que se comportam como as peças de um Lego gigantesco com o qual toda a realidade material em torno de nós é construída. Este é o coração da mecânica quântica."

Calor:

"Aprendemos que uma substância quente é uma substância onde os átomos movem-se com maior rapidez. Mas por que o calor passa das coisas mais quentes àquelas mais frias, e não vice-versa? Por puro acaso. O austríaco Ludwig Boltzmann descobriu que o calor não passa das coisas quentes às mais frias devido a uma lei absoluta: passa apenas com grande probabilidade.

O motivo é que, estatisticamente, é mais provável que um átomo da substância quente, que se move velozmente, bata contra um átomo frio e lhe deixe um pouco da sua energia, e não o contrário."

Uma obra que trata de mecânica quântica, partículas elementares, arquitetura do cosmo e buracos negros, entre outros temas de física teórica, está há meses na lista de livros mais vendidos na Itália.

Capa: Sete Breves Lições de Física. Seven Brief Lessons of Phisycs - Carlo Rovelli.

Vídeo (2 min. 47 seg.): Sete Breves Lições de Física. Seven Brief Lessons of Phisycs - Carlo Rovelli.

Em Sete Breves Lições de Física (publicado no Brasil pela Ed. Objetiva), o professor Carlo Rovelli resume de modo simples os principais conceitos da ciência contemporânea, desde a teoria da relatividade geral de Albert Einstein, passando pelas descobertas do astrofísico inglês Stephen Hawking, até a provável extinção da espécie humana.

"A maior parte dos livros de física são escritos para quem já é apaixonado pelo assunto e quer saber mais. Por isso, pensei num livro para quem conhece pouco ou nada sobre a matéria. Poupei os detalhes e concentrei-me no essencial", disse o autor à BBC Brasil.

"É como escrever poesia: quanto mais se tira, mais bonita ela fica."

Nascido em Verona, no norte da Itália, e atual responsável pelo centro de pesquisas sobre gravidade quântica da Universidade Aix-Marseille, na França, Rovelli explica que o ensaio não trata apenas de física, mas de temas relacionados à natureza humana.

"O livro oferece uma possível resposta, do ponto de vista científico, às perguntas que todos nós, vez ou outra, nos fazemos durante a nossa vida: 'quem somos?', 'de onde viemos?', 'o que existe além daquilo que enxergamos?'. É a visão de alguém que se esforça para compreender isso tudo."

O sucesso da obra superou as expectativas da editora, que inicialmente havia imprimido três mil cópias. Passado pouco mais de um ano, o livro está em sua 18ª edição, teve 300 mil exemplares vendidos no país e foi traduzido para 28 idiomas.

Relatividade no horário nobre

"Logo depois do lançamento, comecei a receber e-mails de leitores entusiasmados, dizendo que comprariam outros exemplares para darem de presente. Em pouco tempo, o título apareceu na lista dos mais vendidos, algo estranho para uma obra de física teórica e, a partir daí, a coisa explodiu: editoras, jornais, rádios e revistas começaram a me procurar."

O professor, de 59 anos, chegou a falar sobre a teoria da relatividade de Einstein e de gravidade quântica em programas do horário nobre da televisão italiana. "Na verdade, as TVs passaram a me convidar só depois que o livro fez sucesso. Do contrário, acho que não teriam dado espaço para assuntos difíceis como este."

Também nas escolas, segundo Rovelli, falar sobre física é quase sempre "chato".

"Os períodos de férias são os melhores para se estudar, porque não há a distração da escola", diz, em um trecho do livro sobre o período em que era estudante universitário e, em uma praia da Calábria, leu pela primeira vez "a mais bela das teorias" (a da relatividade, de Albert Einstein), em um livro roído por ratos.

"Em vez de programas curriculares muito extensos e precisos, para atrair o interesse dos jovens pela ciência é necessário tratar bem os professores e deixar que eles tenham mais liberdade para abordarem os temas que mais gostam. O que faz um aluno se apaixonar por uma determinada matéria é o entusiasmo do próprio professor", afirma.

"Para compreender a ciência é preciso um pouco de empenho e esforço, mas o prêmio é a beleza. E olhos novos para enxergar o mundo."

Confira alguns trechos das explicações de Rovelli sobre personagens, teorias e conceitos da física:

Copérnico:

"Se eu quiser explicar a Revolução Copernicana, posso falar durante horas, apresentar cálculos e citar exemplos. Mas também posso dizer apenas que (Nicolau) Copérnico descobriu que a Terra gira em torno do Sol, e não o contrário. Este é o coração da descoberta, e isto as pessoas entendem."

Darwin:

"Outra extraordinária descoberta científica que pode ser explicada em poucas palavras é a teoria de (Charles) Darwin, que escreveu um livro difícil com pesquisas de observação, mas cuja revelação é simples: os seres humanos e todos os animais e plantas têm os mesmos antepassados, somos todos parentes."

Teoria da relatividade geral:

"Albert Einstein descobriu que o tempo e o espaço não são como acreditávamos até então. Ele nos ensinou que o tempo passa mais rápido no alto e mais lento embaixo, perto da Terra. Por isso, se dois irmão gêmeos viverem em lugares diferentes, um próximo ao mar e outro em montanha, e se reencontrarem depois de cinquenta anos, o que morava na montanha será um pouquinho mais velho que o irmão. Esta diferença pode ser medida até mesmo a uma altura de 30 centímetros do chão.

Einstein ensinou também que o espaço e a força de gravidade (descoberta por Newton) são a mesma coisa. O espaço não é mais diferente da matéria. É uma entidade que oscila, se dobra, se inclina e se torce. Como uma bolinha que roda dentro de um funil, não existem forças misteriosas geradas no centro do objeto, é a curva das paredes do funil que faz com que a bolinha rode. Do mesmo modo, os planetas giram em torno ao Sol e as coisas caem porque o espaço se inclina."

Tempo:

"Não existe ainda uma resposta final da ciência sobre o que é o tempo. Em todo caso, podemos dizer que ele não passa se nada acontece. O tempo não existe por si só, mas é ligado ao modo como as coisas se relacionam umas com as outras. Em vez de dizer que hoje peguei o avião às oito da manhã para vir a Roma, posso dizer que peguei o avião quando o Sol estava a uma certa altura e cheguei quando o Sol estava em outra posição. O tempo não é fundamental para o universo, é possível descrever a natureza sem usar o conceito de tempo."

Buracos negros:

"Quando uma grande estrela queima todo o seu combustível (hidrogênio), acaba por apagar-se. O que resta, então, não é mais suportado pelo calor da combustão e cai esmagado pelo seu próprio peso, inclinando o espaço tão fortemente a ponto de afundar dentro de um verdadeiro buraco. Estes são os famosos buracos negros."

Partículas elementares:

"O mundo é feito de pequenas entidades, os 'quanta', que vibram e saltam de lugar a outro. Existem menos de uma dezena de tipos de partículas elementares. Um punhado de ingredientes elementares que se comportam como as peças de um Lego gigantesco com o qual toda a realidade material em torno de nós é construída. Este é o coração da mecânica quântica."

Calor:

"Aprendemos que uma substância quente é uma substância onde os átomos movem-se com maior rapidez. Mas por que o calor passa das coisas mais quentes àquelas mais frias, e não vice-versa? Por puro acaso. O austríaco Ludwig Boltzmann descobriu que o calor não passa das coisas quentes às mais frias devido a uma lei absoluta: passa apenas com grande probabilidade.

O motivo é que, estatisticamente, é mais provável que um átomo da substância quente, que se move velozmente, bata contra um átomo frio e lhe deixe um pouco da sua energia, e não o contrário."

* * *

06 novembro 2016

THE RIME OF THE ANCIENT MARINER (Coleridge) (Part the Seventh)

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (in Seven Parts)

Part the Seventh.

The Hermit of the Wood.

This Hermit good lives in that wood

Which slopes down to the sea.

How loudly his sweet voice he rears!

He loves to talk with marineres

That come from a far countree.

He kneels at morn and noon and eve—

He hath a cushion plump:

It is the moss that wholly hides

The rotted old oak-stump.

The skiff-boat neared: I heard them talk,

“Why this is strange, I trow!

Where are those lights so many and fair,

That signal made but now?”

Approacheth the ship with wonder.

“Strange, by my faith!” the Hermit said—

“And they answered not our cheer!

The planks looked warped! and see those sails,

How thin they are and sere!

I never saw aught like to them,

Unless perchance it were

“Brown skeletons of leaves that lag

My forest-brook along;

When the ivy-tod is heavy with snow,

And the owlet whoops to the wolf below,

That eats the she-wolf's young.”

“Dear Lord! it hath a fiendish look—

(The Pilot made reply)

I am a-feared”—“Push on, push on!”

Said the Hermit cheerily.

The boat came closer to the ship,

But I nor spake nor stirred;

The boat came close beneath the ship,

And straight a sound was heard.

The ship suddenly sinketh.

Under the water it rumbled on,

Still louder and more dread:

It reached the ship, it split the bay;

The ship went down like lead.

The ancient Mariner is saved in the Pilot's boat.

Stunned by that loud and dreadful sound,

Which sky and ocean smote,

Like one that hath been seven days drowned

My body lay afloat;

But swift as dreams, myself I found

Within the Pilot's boat.

Upon the whirl, where sank the ship,

The boat spun round and round;

And all was still, save that the hill

Was telling of the sound.

I moved my lips—the Pilot shrieked

And fell down in a fit;

The holy Hermit raised his eyes,

And prayed where he did sit.

I took the oars: the Pilot's boy,

Who now doth crazy go,

Laughed loud and long, and all the while

His eyes went to and fro.

“Ha! ha!” quoth he, “full plain I see,

The Devil knows how to row.”

And now, all in my own countree,

I stood on the firm land!

The Hermit stepped forth from the boat,

And scarcely he could stand.

The ancient Mariner earnestly entreateth the Hermit to shrieve him; and the penance of life falls on him.

“O shrieve me, shrieve me, holy man!”

The Hermit crossed his brow.

“Say quick,” quoth he, “I bid thee say—

What manner of man art thou?”

Forthwith this frame of mine was wrenched

With a woeful agony,

Which forced me to begin my tale;

And then it left me free.

And ever and anon throughout his future life an agony constraineth him to travel from land to land;

Since then, at an uncertain hour,

That agony returns;

And till my ghastly tale is told,

This heart within me burns.

I pass, like night, from land to land;

I have strange power of speech;

That moment that his face I see,

I know the man that must hear me:

To him my tale I teach.

What loud uproar bursts from that door!

The wedding-guests are there:

But in the garden-bower the bride

And bride-maids singing are:

And hark the little vesper bell,

Which biddeth me to prayer!

O Wedding-Guest! this soul hath been

Alone on a wide wide sea:

So lonely 'twas, that God himself

Scarce seemed there to be.

O sweeter than the marriage-feast,

'Tis sweeter far to me,

To walk together to the kirk

With a goodly company!—

To walk together to the kirk,

And all together pray,

While each to his great Father bends,

Old men, and babes, and loving friends,

And youths and maidens gay!

And to teach, by his own example, love and reverence to all things that God made and loveth.

Farewell, farewell! but this I tell

To thee, thou Wedding-Guest!

He prayeth well, who loveth well

Both man and bird and beast.

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us

He made and loveth all.

The Mariner, whose eye is bright,

Whose beard with age is hoar,

Is gone: and now the Wedding-Guest

Turned from the bridegroom's door.

He went like one that hath been stunned,

And is of sense forlorn:

A sadder and a wiser man,

He rose the morrow morn.

Part the Seventh.

The Hermit of the Wood.

This Hermit good lives in that wood

Which slopes down to the sea.

How loudly his sweet voice he rears!

He loves to talk with marineres

That come from a far countree.

He kneels at morn and noon and eve—

He hath a cushion plump:

It is the moss that wholly hides

The rotted old oak-stump.

The skiff-boat neared: I heard them talk,

“Why this is strange, I trow!

Where are those lights so many and fair,

That signal made but now?”

The story concluded, the wedding guest leaves "a sadder and wiser man".

Approacheth the ship with wonder.

“Strange, by my faith!” the Hermit said—

“And they answered not our cheer!

The planks looked warped! and see those sails,

How thin they are and sere!

I never saw aught like to them,

Unless perchance it were

“Brown skeletons of leaves that lag

My forest-brook along;

When the ivy-tod is heavy with snow,

And the owlet whoops to the wolf below,

That eats the she-wolf's young.”

“Dear Lord! it hath a fiendish look—

(The Pilot made reply)

I am a-feared”—“Push on, push on!”

Said the Hermit cheerily.

The boat came closer to the ship,

But I nor spake nor stirred;

The boat came close beneath the ship,

And straight a sound was heard.

The ship suddenly sinketh.

Under the water it rumbled on,

Still louder and more dread:

It reached the ship, it split the bay;

The ship went down like lead.

The ancient Mariner is saved in the Pilot's boat.

Stunned by that loud and dreadful sound,

Which sky and ocean smote,

Like one that hath been seven days drowned

My body lay afloat;

But swift as dreams, myself I found

Within the Pilot's boat.

Upon the whirl, where sank the ship,

The boat spun round and round;

And all was still, save that the hill

Was telling of the sound.

I moved my lips—the Pilot shrieked

And fell down in a fit;

The holy Hermit raised his eyes,

And prayed where he did sit.

I took the oars: the Pilot's boy,

Who now doth crazy go,

Laughed loud and long, and all the while

His eyes went to and fro.

“Ha! ha!” quoth he, “full plain I see,

The Devil knows how to row.”

And now, all in my own countree,

I stood on the firm land!

The Hermit stepped forth from the boat,

And scarcely he could stand.

The ancient Mariner earnestly entreateth the Hermit to shrieve him; and the penance of life falls on him.

“O shrieve me, shrieve me, holy man!”

The Hermit crossed his brow.

“Say quick,” quoth he, “I bid thee say—

What manner of man art thou?”

Forthwith this frame of mine was wrenched

With a woeful agony,

Which forced me to begin my tale;

And then it left me free.

And ever and anon throughout his future life an agony constraineth him to travel from land to land;

Since then, at an uncertain hour,

That agony returns;

And till my ghastly tale is told,

This heart within me burns.

I pass, like night, from land to land;

I have strange power of speech;

That moment that his face I see,

I know the man that must hear me:

To him my tale I teach.

What loud uproar bursts from that door!

The wedding-guests are there:

But in the garden-bower the bride

And bride-maids singing are:

And hark the little vesper bell,

Which biddeth me to prayer!

O Wedding-Guest! this soul hath been

Alone on a wide wide sea:

So lonely 'twas, that God himself

Scarce seemed there to be.

O sweeter than the marriage-feast,

'Tis sweeter far to me,

To walk together to the kirk

With a goodly company!—

To walk together to the kirk,

And all together pray,

While each to his great Father bends,

Old men, and babes, and loving friends,

And youths and maidens gay!

And to teach, by his own example, love and reverence to all things that God made and loveth.

Farewell, farewell! but this I tell

To thee, thou Wedding-Guest!

He prayeth well, who loveth well

Both man and bird and beast.

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us

He made and loveth all.

The Mariner, whose eye is bright,

Whose beard with age is hoar,

Is gone: and now the Wedding-Guest

Turned from the bridegroom's door.

He went like one that hath been stunned,

And is of sense forlorn:

A sadder and a wiser man,

He rose the morrow morn.

THE RIME OF THE ANCIENT MARINER (Coleridge) (Part the Sixth)

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (in Seven Parts)

Part the Sixth.

FIRST VOICE.

But tell me, tell me! speak again,

Thy soft response renewing—

What makes that ship drive on so fast?

What is the Ocean doing?

SECOND VOICE.

Still as a slave before his lord,

The Ocean hath no blast;

His great bright eye most silently

Up to the Moon is cast—

If he may know which way to go;

For she guides him smooth or grim

See, brother, see! how graciously

She looketh down on him.

The Mariner hath been cast into a trance; for the angelic power causeth the ves sel to drive northward faster than human life could endure.

FIRST VOICE.

But why drives on that ship so fast,

Without or wave or wind?

SECOND VOICE.

The air is cut away before,

And closes from behind.

Fly, brother, fly! more high, more high

Or we shall be belated:

For slow and slow that ship will go,

When the Mariner's trance is abated.

The supernatural motion is retarded; the Mariner awakes, and his penance begins anew.

I woke, and we were sailing on

As in a gentle weather:

'Twas night, calm night, the Moon was high;

The dead men stood together.

All stood together on the deck,

For a charnel-dungeon fitter:

All fixed on me their stony eyes,

That in the Moon did glitter.

The pang, the curse, with which they died,

Had never passed away:

I could not draw my eyes from theirs,

Nor turn them up to pray.

The curse is finally expiated.

And now this spell was snapt: once more

I viewed the ocean green.

And looked far forth, yet little saw

Of what had else been seen—

Like one that on a lonesome road

Doth walk in fear and dread,

And having once turned round walks on,

And turns no more his head;

Because he knows, a frightful fiend

Doth close behind him tread.

But soon there breathed a wind on me,

Nor sound nor motion made:

Its path was not upon the sea,

In ripple or in shade.

It raised my hair, it fanned my cheek

Like a meadow-gale of spring—

It mingled strangely with my fears,

Yet it felt like a welcoming.

Swiftly, swiftly flew the ship,

Yet she sailed softly too:

Sweetly, sweetly blew the breeze—

On me alone it blew.(460)

And the ancient Mariner beholdeth his native country.

Oh! dream of joy! is this indeed

The light-house top I see?

Is this the hill? is this the kirk?

Is this mine own countree!

We drifted o'er the harbour-bar,

And I with sobs did pray—

O let me be awake, my God!

Or let me sleep alway.

The harbour-bay was clear as glass,

So smoothly it was strewn!

And on the bay the moonlight lay,

And the shadow of the Moon.

The rock shone bright, the kirk no less,

That stands above the rock:

The moonlight steeped in silentness

The steady weathercock.

The angelic spirits leave the dead bodies,

And the bay was white with silent light,

Till rising from the same,

Full many shapes, that shadows were,

In crimson colours came.

And appear in their own forms of light.

A little distance from the prow

Those crimson shadows were:

I turned my eyes upon the deck—

Oh, Christ! what saw I there!

Each corse lay flat, lifeless and flat,

And, by the holy rood!

A man all light, a seraph-man,

On every corse there stood.

This seraph band, each waved his hand:

It was a heavenly sight!

They stood as signals to the land,

Each one a lovely light:

This seraph-band, each waved his hand,

No voice did they impart—

No voice; but oh! the silence sank

Like music on my heart.

But soon I heard the dash of oars;

I heard the Pilot's cheer;

My head was turned perforce away,

And I saw a boat appear.

The Pilot, and the Pilot's boy,

I heard them coming fast:

Dear Lord in Heaven! it was a joy

The dead men could not blast.

I saw a third—I heard his voice:

It is the Hermit good!

He singeth loud his godly hymns

That he makes in the wood.

He'll shrieve my soul, he'll wash away

The Albatross's blood.

Part the Sixth.

FIRST VOICE.

But tell me, tell me! speak again,

Thy soft response renewing—

What makes that ship drive on so fast?

What is the Ocean doing?

SECOND VOICE.

Still as a slave before his lord,

The Ocean hath no blast;

His great bright eye most silently

Up to the Moon is cast—

If he may know which way to go;

For she guides him smooth or grim

See, brother, see! how graciously

She looketh down on him.

Now the mariner is free from curse & he's abble to pray.

The Mariner hath been cast into a trance; for the angelic power causeth the ves sel to drive northward faster than human life could endure.

FIRST VOICE.

But why drives on that ship so fast,

Without or wave or wind?

SECOND VOICE.

The air is cut away before,

And closes from behind.

Fly, brother, fly! more high, more high

Or we shall be belated:

For slow and slow that ship will go,

When the Mariner's trance is abated.

The supernatural motion is retarded; the Mariner awakes, and his penance begins anew.

I woke, and we were sailing on

As in a gentle weather:

'Twas night, calm night, the Moon was high;

The dead men stood together.

All stood together on the deck,

For a charnel-dungeon fitter:

All fixed on me their stony eyes,

That in the Moon did glitter.

The pang, the curse, with which they died,

Had never passed away:

I could not draw my eyes from theirs,

Nor turn them up to pray.

The curse is finally expiated.

And now this spell was snapt: once more

I viewed the ocean green.

And looked far forth, yet little saw

Of what had else been seen—

Like one that on a lonesome road

Doth walk in fear and dread,

And having once turned round walks on,

And turns no more his head;

Because he knows, a frightful fiend

Doth close behind him tread.

But soon there breathed a wind on me,

Nor sound nor motion made:

Its path was not upon the sea,

In ripple or in shade.

It raised my hair, it fanned my cheek

Like a meadow-gale of spring—

It mingled strangely with my fears,

Yet it felt like a welcoming.

Swiftly, swiftly flew the ship,

Yet she sailed softly too:

Sweetly, sweetly blew the breeze—

On me alone it blew.(460)

And the ancient Mariner beholdeth his native country.

Oh! dream of joy! is this indeed

The light-house top I see?

Is this the hill? is this the kirk?

Is this mine own countree!

We drifted o'er the harbour-bar,

And I with sobs did pray—

O let me be awake, my God!

Or let me sleep alway.

The harbour-bay was clear as glass,

So smoothly it was strewn!

And on the bay the moonlight lay,

And the shadow of the Moon.

The rock shone bright, the kirk no less,

That stands above the rock:

The moonlight steeped in silentness

The steady weathercock.

The angelic spirits leave the dead bodies,

And the bay was white with silent light,

Till rising from the same,

Full many shapes, that shadows were,

In crimson colours came.

And appear in their own forms of light.

A little distance from the prow

Those crimson shadows were:

I turned my eyes upon the deck—

Oh, Christ! what saw I there!

Each corse lay flat, lifeless and flat,

And, by the holy rood!

A man all light, a seraph-man,

On every corse there stood.

This seraph band, each waved his hand:

It was a heavenly sight!

They stood as signals to the land,

Each one a lovely light:

This seraph-band, each waved his hand,

No voice did they impart—

No voice; but oh! the silence sank

Like music on my heart.

But soon I heard the dash of oars;

I heard the Pilot's cheer;

My head was turned perforce away,

And I saw a boat appear.

The Pilot, and the Pilot's boy,

I heard them coming fast:

Dear Lord in Heaven! it was a joy

The dead men could not blast.

I saw a third—I heard his voice:

It is the Hermit good!

He singeth loud his godly hymns

That he makes in the wood.

He'll shrieve my soul, he'll wash away

The Albatross's blood.

THE RIME OF THE ANCIENT MARINER (Coleridge) (Part the Fifth)

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (in Seven Parts)

Part the Fifth.

Oh sleep! it is a gentle thing,

Beloved from pole to pole!

To Mary Queen the praise be given!

She sent the gentle sleep from Heaven,

That slid into my soul.

By grace of the holy Mother, the ancient Mariner is refreshed with rain.

The silly buckets on the deck,

That had so long remained,

I dreamt that they were filled with dew;

And when I awoke, it rained.

My lips were wet, my throat was cold,

My garments all were dank;

Sure I had drunken in my dreams,

And still my body drank.

I moved, and could not feel my limbs:

I was so light—almost

I thought that I had died in sleep,

And was a blessed Ghost.

He heareth sounds and seeth strange sights and commotions in the sky and the element.

And soon I heard a roaring wind:

It did not come anear;

But with its sound it shook the sails,

That were so thin and sere.

The upper air burst into life!

And a hundred fire-flags sheen,

To and fro they were hurried about!

And to and fro, and in and out,

The wan stars danced between.

And the coming wind did roar more loud,

And the sails did sigh like sedge;

And the rain poured down from one black cloud;

The Moon was at its edge.

The thick black cloud was cleft and still

The Moon was at its side:

Like waters shot from some high crag,

The lightning fell with never a jag,

A river steep and wide.

The bodies of the ship's crew are inspired, and the ship moves on;

The loud wind never reached the ship,

Yet now the ship moved on!

Beneath the lightning and the Moon

The dead men gave a groan.

They groaned, they stirred, they all uprose,

Nor spake, nor moved their eyes;

It had been strange, even in a dream,

To have seen those dead men rise.

The helmsman steered, the ship moved on;

Yet never a breeze up-blew;

The mariners all 'gan work the ropes,

Where they were wont to do:

They raised their limbs like lifeless tools—

We were a ghastly crew.

The body of my brother's son,

Stood by me, knee to knee:

The body and I pulled at one rope,

But he said nought to me.

But not by the souls of the men, nor by demons of earth or middle air, but by a blessed troop of angelic spirits, sent down by the invoca tion of the guardian saint.

“I fear thee, ancient Mariner!”

Be calm, thou Wedding-Guest!

'Twas not those souls that fled in pain,

Which to their corses came again,

But a troop of spirits blest:

For when it dawned—they dropped their arms,

And clustered round the mast;

Sweet sounds rose slowly through their mouths,

And from their bodies passed.

Around, around, flew each sweet sound,

Then darted to the Sun;

Slowly the sounds came back again,

Now mixed, now one by one.

Sometimes a-dropping from the sky

I heard the sky-lark sing;

Sometimes all little birds that are,

How they seemed to fill the sea and air

With their sweet jargoning!

And now 'twas like all instruments,

Now like a lonely flute;

And now it is an angel's song,

That makes the Heavens be mute.

It ceased; yet still the sails made on

A pleasant noise till noon,

A noise like of a hidden brook

In the leafy month of June,

That to the sleeping woods all night

Singeth a quiet tune.

Till noon we quietly sailed on,

Yet never a breeze did breathe:

Slowly and smoothly went the ship,

Moved onward from beneath.

The lonesome Spirit from the South Pole carries on the ship as far as the Line, in obedience to the angelic troop, but still requireth vengeance.

Under the keel nine fathom deep,

From the land of mist and snow,

The spirit slid: and it was he

That made the ship to go.

The sails at noon left off their tune,

And the ship stood still also.

The Sun, right up above the mast,

Had fixed her to the ocean:

But in a minute she 'gan stir,

With a short uneasy motion—

Backwards and forwards half her length

With a short uneasy motion.

Then like a pawing horse let go,

She made a sudden bound:

It flung the blood into my head,

And I fell down in a swound.

How long in that same fit I lay,

I have not to declare;

But ere my living life returned,

I heard and in my soul discerned

Two voices in the air.

The Polar Spirit's fellow-demons, the invisible inhabitants of the element, take part in his wrong; and two of them relate, one to the other, that penance long and heavy for the ancient Mariner hath been accorded to the Polar Spirit, who returneth southward.

“Is it he?” quoth one, “Is this the man?

By him who died on cross,

With his cruel bow he laid full low,

The harmless Albatross.

“The spirit who bideth by himself

In the land of mist and snow,

He loved the bird that loved the man

Who shot him with his bow.”

The other was a softer voice,

As soft as honey-dew:

Quoth he, “The man hath penance done,

And penance more will do.”

Part the Fifth.

Oh sleep! it is a gentle thing,

Beloved from pole to pole!

To Mary Queen the praise be given!

She sent the gentle sleep from Heaven,

That slid into my soul.

Gustave Doré's illustration - "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner".

By grace of the holy Mother, the ancient Mariner is refreshed with rain.

The silly buckets on the deck,

That had so long remained,

I dreamt that they were filled with dew;

And when I awoke, it rained.

My lips were wet, my throat was cold,

My garments all were dank;

Sure I had drunken in my dreams,

And still my body drank.

I moved, and could not feel my limbs:

I was so light—almost

I thought that I had died in sleep,

And was a blessed Ghost.

He heareth sounds and seeth strange sights and commotions in the sky and the element.

And soon I heard a roaring wind:

It did not come anear;

But with its sound it shook the sails,

That were so thin and sere.

The upper air burst into life!

And a hundred fire-flags sheen,

To and fro they were hurried about!

And to and fro, and in and out,

The wan stars danced between.

And the coming wind did roar more loud,

And the sails did sigh like sedge;

And the rain poured down from one black cloud;

The Moon was at its edge.

The thick black cloud was cleft and still

The Moon was at its side:

Like waters shot from some high crag,

The lightning fell with never a jag,

A river steep and wide.

The bodies of the ship's crew are inspired, and the ship moves on;

The loud wind never reached the ship,

Yet now the ship moved on!

Beneath the lightning and the Moon

The dead men gave a groan.

They groaned, they stirred, they all uprose,

Nor spake, nor moved their eyes;

It had been strange, even in a dream,

To have seen those dead men rise.

The helmsman steered, the ship moved on;

Yet never a breeze up-blew;

The mariners all 'gan work the ropes,

Where they were wont to do:

They raised their limbs like lifeless tools—

We were a ghastly crew.

The body of my brother's son,

Stood by me, knee to knee:

The body and I pulled at one rope,

But he said nought to me.

But not by the souls of the men, nor by demons of earth or middle air, but by a blessed troop of angelic spirits, sent down by the invoca tion of the guardian saint.

“I fear thee, ancient Mariner!”

Be calm, thou Wedding-Guest!

'Twas not those souls that fled in pain,

Which to their corses came again,

But a troop of spirits blest:

For when it dawned—they dropped their arms,

And clustered round the mast;

Sweet sounds rose slowly through their mouths,

And from their bodies passed.

Around, around, flew each sweet sound,

Then darted to the Sun;

Slowly the sounds came back again,

Now mixed, now one by one.

Sometimes a-dropping from the sky

I heard the sky-lark sing;

Sometimes all little birds that are,

How they seemed to fill the sea and air

With their sweet jargoning!

And now 'twas like all instruments,

Now like a lonely flute;

And now it is an angel's song,

That makes the Heavens be mute.

It ceased; yet still the sails made on

A pleasant noise till noon,

A noise like of a hidden brook

In the leafy month of June,

That to the sleeping woods all night

Singeth a quiet tune.

Till noon we quietly sailed on,

Yet never a breeze did breathe:

Slowly and smoothly went the ship,

Moved onward from beneath.

The lonesome Spirit from the South Pole carries on the ship as far as the Line, in obedience to the angelic troop, but still requireth vengeance.

Under the keel nine fathom deep,

From the land of mist and snow,

The spirit slid: and it was he

That made the ship to go.

The sails at noon left off their tune,

And the ship stood still also.

The Sun, right up above the mast,

Had fixed her to the ocean:

But in a minute she 'gan stir,

With a short uneasy motion—

Backwards and forwards half her length

With a short uneasy motion.

Then like a pawing horse let go,

She made a sudden bound:

It flung the blood into my head,

And I fell down in a swound.

How long in that same fit I lay,

I have not to declare;

But ere my living life returned,

I heard and in my soul discerned

Two voices in the air.

The Polar Spirit's fellow-demons, the invisible inhabitants of the element, take part in his wrong; and two of them relate, one to the other, that penance long and heavy for the ancient Mariner hath been accorded to the Polar Spirit, who returneth southward.

“Is it he?” quoth one, “Is this the man?

By him who died on cross,

With his cruel bow he laid full low,

The harmless Albatross.

“The spirit who bideth by himself

In the land of mist and snow,

He loved the bird that loved the man

Who shot him with his bow.”

The other was a softer voice,

As soft as honey-dew:

Quoth he, “The man hath penance done,

And penance more will do.”